Adaptations: Enabling a sustainable supply of private rented options

The PRS is changing – the profile of tenants is becoming older and more households stay in the PRS for much longer. Further, with twice the proportion of households in the PRS than at the turn of the century, it follows that increasing numbers tenant households will have a family member with some form of disability.

This means landlords are increasingly likely to face requests to make adaptations to property enabling individuals who are elderly or have a disability to live at home in a safe, comfortable environment.

This post sets out the experiences of landlords and the practicalities they face in trying to meet these requests. It finds there is opportunity for local authorities, the voluntary sector and private landlords to work together. This could be an opportunity to use licensing revenues constructively and raise the PRS offer to particular groups of residents.

Introduction

The Private Rented Sector (PRS) is expanding as a sector. It is increasingly housing more older people and longer-term tenancies are becoming more common. As the tenant-base diversifies, so too should the supply of homes in the PRS.

One aspect of the increasing diversification of demand is the provision of homes which cater for tenants with accessibility needs. With housing supply in both the owner-occupied and social housing sectors falling short of demand, it is the PRS which is increasingly relied upon to meet the nation’s housing needs.

The RLA’s Quarter 4 State of the PRS report Property Standards and Investment asked landlords about the costs, support and key investments they had made in their properties to make their properties accessible to tenants with specific additional needs.

The NLA has also done much work on the demand and the barriers landlords face in supporting tenants who require property adaptations in the PRS. This post reviews evidence and sets out the support landlords need to ensure the housing needs of those groups who require such support can be met.

Demand for adaptations

Despite an increasing level of tenant demand for accessibility adaptations – see this report for example – most (78.8%) landlords in our Quarter 4 survey stated they had never been asked to make adaptations to their properties (78.8%).

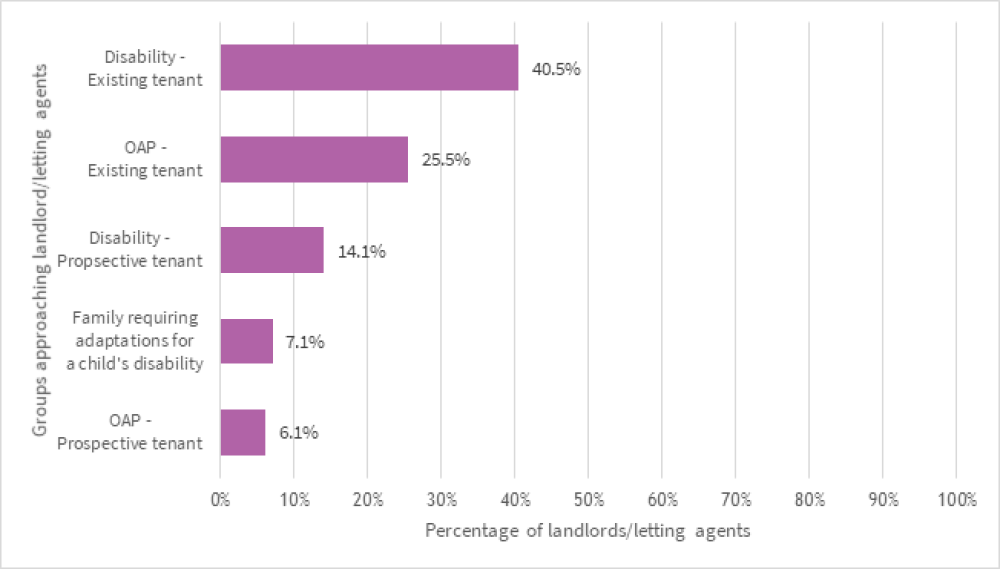

Those landlords who had received requests for adaptations identified the broad tenant group who had made the request:

Chart 1: Tenants requiring accessibility adaptations

Chart 1 shows:

- Most landlords identified adaptation requests originating from either sitting or prospective tenants who need to support a resident with physical disabilities (61.7%).

- Almost one-third of respondents identified old age pensioners (OAPs) as the primary group of residents requesting property adaptations (31.6%).

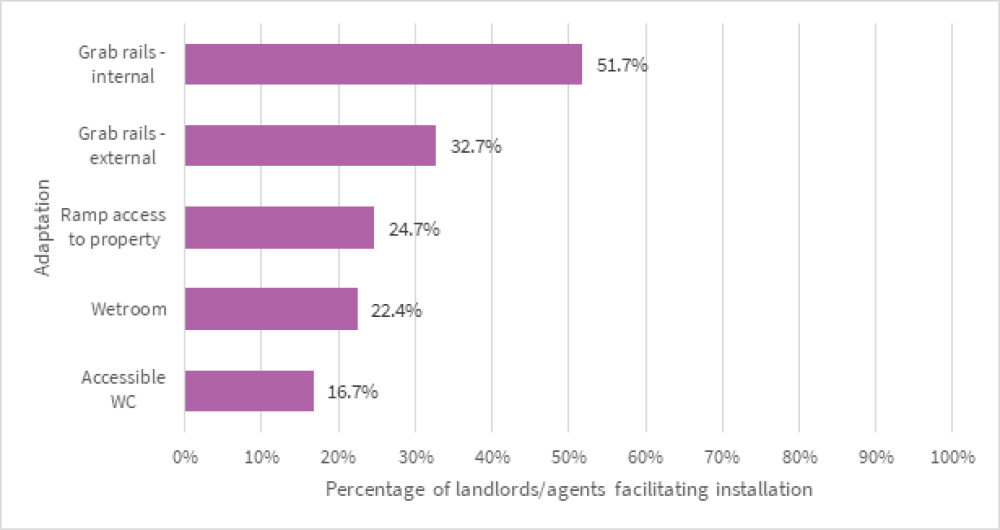

When landlords were asked which adaptations they had made, the items most commonly identified from a longer list were as follows:

Chart 2: Property adaptations made by landlords (multiple responses)

The most common property adaptations were generic adaptations such as grab rails and ramp access. This was followed by bathroom alterations, which again would cover the needs of several groups.

Meeting the cost of adaptations – before and after strategies

Adaptations require investment. It requires investment to install adaptations, investment to maintain them to ensure they remain safe.

Finally, once the tenant who requires the investment vacates the property, the landlords will typically anticipate there being a cost to remove those adaptations and prepare the property for new tenants.

Landlords were asked who met the costs of making property adaptations. They responded as follows:

- Landlords – 49.0%.

- Local authority – 25.5%.

- Tenant – 4.6%.

- The NHS – 2.7%.

- A charity or other benefactor – 1.9%.

- A combination of the above – 10.3% (in most of these cases, the landlords were expected to meet at least some of the cost).

These results show that the majority of landlords (including landlords in the final group) making adaptations to their properties are having to pay for these adaptations out of their own pockets.

A key reason for doing so is their belief that in accommodating tenants with adaptations, those tenants will stay longer in the property – almost half of landlords (45.8%) agreed with the statement “Tenants whose rented home has their required adaptations will stay for longer”.

So, the evidence suggests landlords are willing to make adaptations. However, landlords then often believe they are expected to meet the costs of the removal of the adaptations:

Landlords were asked what would happen to these adaptations once the tenant who required them had vacated the property:

- Landlord will pay to remove adaptations and redecorate (24.4%).

- No idea – no agreement (24.1%).

- Landlord will leave adaptations in situ and look for a tenant who requires similar (23.7%).

- Tenant will remove adaptations and redecorate (7.4%).

In addition, almost a quarter of landlords are unsure of how to move forward with their properties once a tenant with accessibility needs has moved out.

Impact of the cost of adaptations

Landlords are simply not being supported in providing for tenants with accessibility needs. They feel adapations must be removed – more than half (51.9%) of landlords agree with the statement: “I worry adaptations will make my property more difficult to let in the future”.

Given the lack of support landlords receive, two statements which were among the most commonly identified by survey participants were:

- “I would take tenants who require adaptations if it were certain the property would be returned in its original condition” (54.0% of all landlords agreed with this statement).

- “Were there more financial support and advice for landlords I may be more willing to take on tenants who require adaptations.” (46.4% agreed).

NLA Research

These findings are reinforced by research undertaken by the National Landlords Association. They had commissioned research into property adaptations, attempting to gauge how their membership has approached this issue.

Both RLA and NLA research points outshows that the majority of landlords do not let to tenants with accessibility needs simply because they have never been asked to.

The NLA for example found 49% of landlords were willing to let to tenants who would require adaptations. They also found this proportion rose to 68% if there were some support – the research specified a grant – which would assist in the cost of the installation of those adaptations.

In both pieces of research, landlords cited costs as the most common barrier, with landlords unwilling to invest in adaptations for their property only to be left facing more bills once the tenancy ends.

In the RLA survey landlords made the following comments:

A tenant, relying on assistance, does not 'see' maintenance [costs] and this makes repairs much more expensive.

Have rented to charity organisations in past - always with promise to return house to original condition. In my experience this does not happen and as a landlord you are left with having to spend £000s in renovation costs

Being responsible for an older person's well-being in your property is not a responsibility I wish to have again

Policy recommendations: Getting ahead of the demand curve

The comments and views of landlords are revealing. Many more landlords would be willing to have adaptations installed if asked – and they are increasingly likely to be asked at some point.

But more support is needed – not just to pay for installations but then to develop a suitable forward strategy beyond the current tenant.

Many recognise having tenants who require adaptations bring a benefit in that they are more likely to stay longer. However, a proper funding and support model is required for landlords to secure their revenue stream as well as meet capital costs.

The Disabled Facilities Grant (DFG) is one route landlords can go down. This fund is administered by local authorities to varying limits across the UK – £30,000 in England, £36,000 in Wales and £25,000 in Northern Ireland. It is clear that landlords are unaware of the fund – despite being eligible, only 7% of funds awarded under the scheme go to PRS-tenured properties.

Grant-support and awareness is not the only opportunity however:

With the changing demographics of tenants in the PRS there are emerging opportunities to let converted property to a stream of tenants with specific needs. There is however an information asymmetry – there are difficulties in matching landlords who find themselves with adapted property to let with prospective new tenants who require such property.

It is clear that there could be a greater role for the public or voluntary sectors in assisting this match – working alongside landlords to ensure the supply of homes in this market is sustained via linking available property to tenants with specific need. Landlords would no longer feel the need to invest in removing adaptations to find new tenants.

Local matching registers could be a positive outcome from local licensing schemes many local authorities are so keen on introducing. If authorities state the aim is to raise the PRS experience, then operating a register or offering landlords with these properties licensing discounts would help achieve these aims.

In doing so, at least landlords with available property could see benefit from their fees. It would also encourage investment to meet these needs.