Capital Gains Tax & the PRS - negative impacts on the property market

The volume of properties bought and sold has scarcely changed since 1995 – yet over 3 million new homes have been built in this time.

Research from the RLA reports on the impact of Capital Gains Tax. The tax traps landlords into holding property longer than they wish, and so holds back a functioning property market. The tax reduces property investment as well as the volume of properties available to purchase.

Introduction

In April this year the Financial Times (24/19/20) reported a “bumper” rise in Capital Gains Tax (CGT) receipts. The article puts this rise in CGT receipts as being largely due to the sale of Buy-to-Let (BTL) property by UK landlords.

The FT emphasises the squeeze landlords are being put under as they face a perfect storm of (1) increases in CGT; (2) the phasing out of higher rate tax relief on mortgage interest, and, (3) increased regulation.

This post focuses on the effects of CGT – specifically how it impacts on landlords, and the wider housing market.

The effects of Capital Gains Tax

High CGT tax rates mean landlords in the Private Rented Sector (PRS) will often adopt one or more of the following strategies:

First: landlords may opt to hold on to property beyond the time they had initially anticipated in the hope of a future relief scheme or reform of CGT.

Secondly, landlords who entered the PRS market with the aim to sell property on retirement in place of a pension may opt instead to use the rental income as a pension and decide to leave the property as a legacy. Property owners can then shield the property through perfectly legal Inheritance Tax (IHT) schemes.

Thirdly, property owners could create more complex, company-based, methods of holding property. This could be via a UK or an overseas (offshore) vehicle. Creation of limited companies again enables landlords to legitimately reduce some tax liabilities. Though CGT is itself not necessarily avoidable, use of a company vehicle can shift the tax balance.

However, in each of these cases the result is that property remains in the same landlords’ possession for much longer than anticipated.

This means CGT is acting as a barrier to a functioning housing market – one in which landlords in the PRS can adjust their portfolios in line with their views and experience of market conditions.

Impact of Capital Gains Tax on the PRS

One conventional argument to reduce taxes such as CGT is that by reducing tax rates, tax revenues into government coffers rise. The “bumper” rise in tax take indicates raising CGT has NOT led to reduced receipts – far from it.

However, there are two reasons why CGT should not be seen as an easy win with no consequences:

Firstly, a key reason is one of equity. Landlords, though they are entrepreneurs, are not entitled to the same CGT breaks as other small business owners – who can for example claim Entrepreneurs’ Relief on asset sales. There is an inherent unfairness towards landlords in the CGT system.

The second reason is to stimulate the housing market. ‘Stimulate’ does not necessarily mean raise prices, though that is a common interpretation. Here it means to introduce greater dynamism and volume. The volume of properties traded in 2018 – approx. 660,000 (freehold) in England & Wales – is not that much greater than in 1995 when 638,000 freehold properties were traded: Yet, since 1995, government figures indicate over 3 MILLION new homes in England & Wales have been built.

Too often low trading volumes for property have been put down to cyclical factors based on relative economic strength from period to period. There is however a structural component to the low volumes too. It has long been argued by organisations such as the RLA that CGT is in fact a disincentive on landlords to either sell or invest in, their largest business asset: where the return on investment in a property leads to an increase in tax, and cannot be offset elsewhere, investment is discouraged.

The overall result is that CGT policy is leading to not only a sub-optimal allocation of the UK housing stock across tenures, it is also being a disincentive on housing stock investment.

With housing being held by landlords for longer, the conclusion is that CGT is an obstacle to the availability of homes for owner occupation.

NRLA members and current thoughts on CGT

The NRLA was recently commissioned by a Westminster-based lobby group to look at Capital Gains Tax in more detail.

Over 2,600 landlords were asked whether they thought Capital Gains Tax was in fact a disincentive for them to sell property:

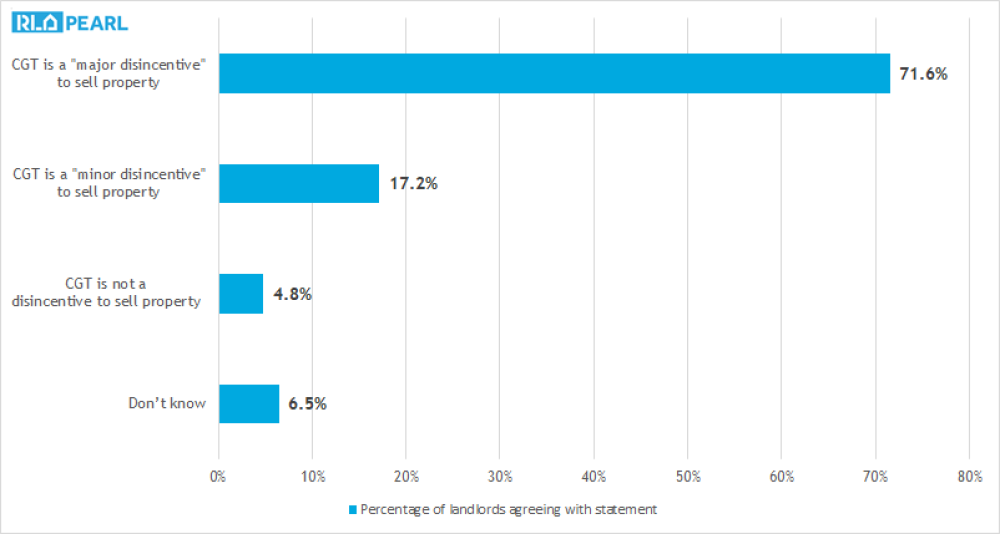

Chart 1: Landlords' views on CGT as a disincentive to sell property

The above shows:

Over 70% (71.6%) of landlords felt that CGT as it now stands was acting as a major disincentive for landlords to sell property on the open market.

Very few landlords (less than 5%) do not see CGT as any kind of disincentive to sell property.

Regional Variations on CGT and the disincentive to sell

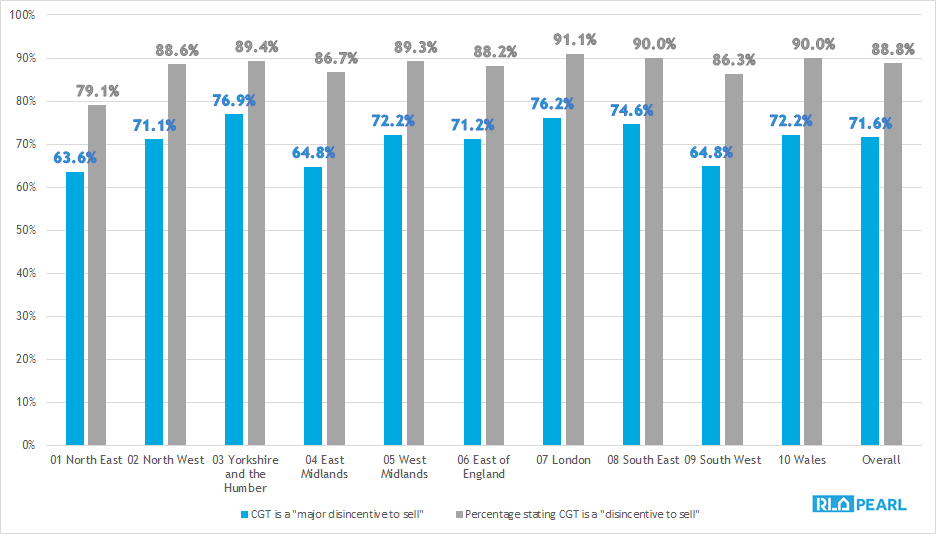

Table 2 below shows the regional variations in responses to the above question. Here, the region refers to the single region identified by the survey participant in which most of his or her properties in the PRS are based.

The Chart distinguishes between those identifying CGT as a “major” disincentive and the aggregate of those stating CGT is either a “major”, or a “minor”, disincentive:

Chart 2: Regional variation between landlords’ views on CGT

The first thing to say is that, right across England and Wales, there is concern about CGT and its impact on the Private Rented Sector.

That said, there is clearly some regional variation in the views of landlords – for example between London and the North East of England.

However, it is the similarity between the regions not the differences which is the noticeable feature of the table. The concern about CGT and how it acts as a barrier to selling property stretches across England and Wales.

Some observations on opinion

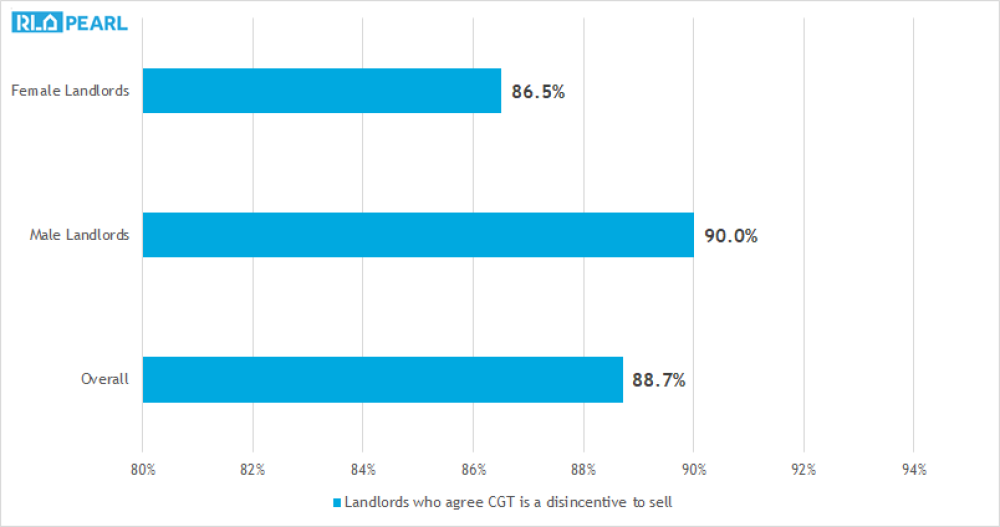

This section looks a little more closely at the views of common groups of landlords identified by our survey: Chart 3 looks at a gender-based analysis of landlords and whether this has an influence on views about CG

Chart 3: Opinion of male and female landlords on CGT

The chart above compares the views of male and female landlords. It shows that male landlords feel more strongly about CGT than female landlords do.

Note that the RLA looked at the results using established statistical techniques. We found there IS a statistically significant difference in the responses: there is evidence to suggest male landlords are more likely to find CGT a disincentive than their female counterparts.

[Note that we also looked at the profile of landlords by age. We compared the Under 55-years against the over 55-years. We then also compared the under 45-years against the over 45-years. In both instances we found there was no significant differences from the overall proportion of landlords who see CGT as a disincentive to sell (approx. 88%)].

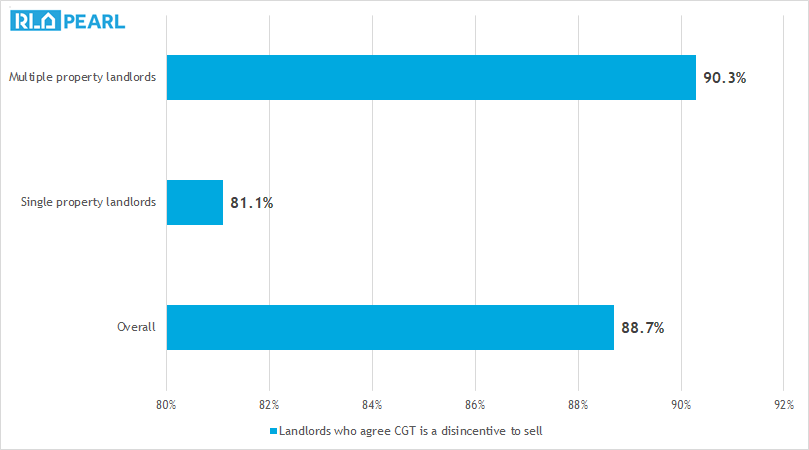

There were also differences in views between those who let a single property and those who had multiple properties to let:

Chart 4: Opinion of landlords who let single, and multiple, properties on CGT

The analysis shows landlords who own multiple properties are statistically more likely to be concerned about CGT as a barrier to selling property.

BUT for landlords of single properties, it is still the case that over 80% find CGT a vexatious issue.

Impact of CGT on business strategy

Finally, we looked at whether there was a difference in attitudes to CGT and the business decisions taken by landlords in respect of their portfolio.

We examined whether views on CGT differed depending on whether a landlord had bought, sold or decided to maintain their portfolios over the last twelve months. We also looked at planned actions over the next twelve months.

There was no difference in views on CGT on the basis of past or planned business strategy: Irrespective of the key business decisions taken, CGT was a major factor in taking that decision.

The RLA’ s quarterly surveys have recently shown:

- Very few landlords expanding their portfolios, and a high proportion holding property.

- There is consistently a pattern of landlords stating they will sell property in the next twelve months, but a much smaller proportion who actually do sell.

This all lends support to the view that, when faced with a potential CGT bill, landlords are opting – reluctantly – to remain in the PRS.

Summary

This paper has outlined the current thoughts of landlords on Capital Gains Tax (CGT).

There can be no doubt from the statistics here that landlords, irrespective of location, gender, portfolio size or business plan see the tax as a disincentive to sell property.

That said there are differences: In the North East, for example, CGT is slightly less of a concern as it is in London.

Female landlords are less vexed about Capital Gains Tax than male landlords. Although the difference appears small it IS statistically significant: it may well be that this insight could form part of a wider discussion into gender-based motivations, behaviours and strategies of landlords.

Finally, landlords who let multiple properties are more likely to see CGT as a disincentive to sell than those landlords who let just the one. Given the FT article, this may indicate that strategies for larger independent landlords to reduce their CGT bills are not satisfactory.

Policy conclusions

The stand-out finding from this analysis however is the consistently high level of concern about CGT and the resulting disincentives to trade assets in the PRS: it does not matter whether a landlord plans to expand, contract or maintain his or her asset base – CGT is apparently always a factor at the forefront of business decision-making.

Reforming CGT will reduce distortions in the residential property market – landlords will be more free to release, rather than hold, property.

The government recognising the role of landlords as entrepreneurs who seek to invest in housing stock without penalty would also be welcome: A more imaginative approach to CGT would also enhance the quality and energy efficiency of homes through encouraging investment without fear of increased taxation once the improved house is sold on.

Finally, developing CGT incentives for buying and selling properties with tenants in situ is a policy which is gathering momentum. Independent Think Tanks such as Onward Research have advocated such CGT discounts.

This approach could be a way to bring together those whose views on the PRS presently appear diametrically opposed: those who advocate a Right to Buy for PRS tenants and those who seek to make housing markets more efficient through elimination of tax disincentives.

This article was written by Nick Clay of the NRLA, the views expressed here are the author’s own, and not necessarily those of the NRLA.

Thanks to Dr David Smith of the NRLA on a previous draft of this article, John Stewart also gave valuable comments. Aidan Crehan of the NRLA provided research assistance. Errors which remain have been made by the author.