The wait of justice: the slow pace of the courts in Greater London

Key findings

- At 30 weeks, wait times for enforcement in London are eight weeks longer than the national average and three times higher than the ideal wait time. This wait time has increased substantially in 2019.

- Rent arrears is the most common reason for serving notice. If a tenant continuously fails to pay rent through the entire repossession process, a landlord in London will lose almost £10k on average before a bailiff enforces the judgement.

- London landlords wait 1.4 weeks longer on average for a court hearing for possession. This gap has widened in 2019.

- A decline in accelerated possession orders has not led to a decline in possession orders from the private rented sector. Instead, there was a 20% increase in private landlord possession cases in Quarter 3 2019 compared to the same quarter in 2018. This suggests that removing section 21 will not lead to a decrease in the number of private landlord possession claims each year.

- There has been a significantly larger increase in the time taken to process applications. Quarter 3 2019 saw a 31% increase in the time taken to complete possession action. This is not explained by a rise in applications for warrants as enforcement numbers fell by 19% in the same period.

Introduction

Between 2010 and 2019 over half the courts in England and Wales were closed as part of either the Court Estate Reform Programme (CERP) or the Estates Reform Project (ERP).

The end goal of the latter programme is to create a justice system that ‘works even better for everyone, from judges and legal professionals, to witnesses, litigants, and the vulnerable victims of crime.’ To support this ambition, the Government is investing £1bn on improving online facilities across the courts to make the whole system more efficient. It is not unreasonable to expect court wait times to fall as the impact of these improvements is felt.

The Government has now announced it plans to remove section 21 notices which is also likely to have an impact on court waiting times. The section 21 notice gives landlords access to the ‘accelerated possession’ route. This is a largely procedural route that requires no court hearing in most circumstances, freeing up court resources and putting less of a strain on the system. If section 21 is removed and landlords still continue to seek possession, the courts will need to be extremely efficient to cope with the increased workload.

Are the efficiency savings working, though? Previous research by the NRLA would suggest not. In the largest ever survey of private landlords, 79% of those who had used the courts were dissatisfied with their experience. Excessive delays were frequently cited as the main cause of this dissatisfaction.

However, landlords rarely seek to repossess their property so much of this dissatisfaction may be based on historical rather than recent experience – just 0.4% of all PRS tenancies were ended by a possession order in Q1-3 2019. Landlord satisfaction may be an inaccurate indicator of success.

To assess how successful these court reforms have been, the NRLA made a series of freedom of information (FOI) requests to the Ministry of Justice (MOJ). These FOIs covered bailiff recruitment rates and court wait times by region. This data covers the period from Quarter 1 2018 to Quarter 3 2019.

This article is the first in a series on our findings. It focuses on the experiences of court users in London in comparison to the rest of England and Wales. It covers both possession orders and the enforcement of these orders by county court bailiffs.

How should the courts be working?

The Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) set out a code of practice for the courts with the objective of ensuring cases are dealt with judiciously and at proportionate cost. One of the key objectives is that cases should be dealt with ‘expeditiously and fairly’. As long as the courts are matching the timeframes laid out in the CPR then it is reasonable to say they are meeting these objectives.

For possession orders the CPR indicates an ideal timeframe that the landlord should expect to wait for an order to be granted. The courts are expected to call a hearing between four and eight weeks after the landlord makes a claim. If the judge is satisfied the landlord is entitled to possession then the possession order should set a date no earlier than 2 weeks after this hearing. If the tenant has still not left after this date then the landlord may apply for a bailiff to enforce the judgement.

The length of time for bailiff enforcement is not covered by the CPR and there is technically no minimum timeframe for enforcement. However, Form N54 is a quasi-legal requirement that effectively creates a 2 week minimum timeframe from applying for a bailiff to their arrival at the property to enforce the judgement.

To account for service and processing of the various documents, it is not unreasonable to add on a further week to the total timeframe. This leaves a timeframe of five to nine weeks for a possession order to be issued. A further four weeks is required for bailiff enforcement which means the whole process should take nine-13 weeks from application to a bailiff enforcing the judgement.

Our previous research has found that landlords are over five times more likely to exclusively use accelerated possession rather than the grounds-based section 8 route which requires a court hearing in person. As this route is predominantly procedural and far simpler for the courts to process, we would expect to see the average times for the issuing of possession orders be in the lower end of the five-nine week timeframe if the courts are working efficiently.

In addition to this, the 18,111 possession orders issued in the previous year is a fractional amount of the 4.5 million households in the private rented sector (PRS). Only 0.4% of tenancies were ended through court action between Q4 2018 and Q3 2019. This low volume of possession action suggests that if the courts are properly resourced, they should not be considered overstretched by landlord claims. As a result, they should be able to deal with cases expeditiously and fairly.

As such, we have set an ideal timeframe of 10 weeks in total from application to possession being enforced as the benchmark for this analysis.

How are the courts working in London?

How often are the courts being used?

The private rented sector in London faces pressures felt in no other region of the country. The proportion of households in the city that are privately rented is 50% higher than the national average. In addition to this, as a proportion of their income tenants in London paid more than twice as much on average as tenants in the north of England in 2016. The NRLA's previous research found that over 80% of those landlords who had served a section 21 notice did so at least in part because of rent arrears.

Due to the proportion of income spent on rent in London it is not unreasonable to anticipate that the incidence of rent arrears would be higher/greater in the capital than elsewhere. It is no surprise then that London makes up a significant proportion of the repossession claims across England. Despite making up only 15% of the population of England and Wales, in the first three quarters of 2019, 29% of all private landlord possession claims were for properties based in London.

What is more, compared to any other region in England & Wales, London has the lowest number of County Courts. This means London is vulnerable to strains resulting from increases in either the volume or the complexity of hearings.

Thus, if private rented sector landlords are prevented from using accelerated possession, and instead have to attend a court hearing to regain possession, the strains on the court system will increase. Put simply, the additional caseload, coupled with the limited amount of time available per day to schedule hearings inevitably leads to court bottlenecks and increased delays.

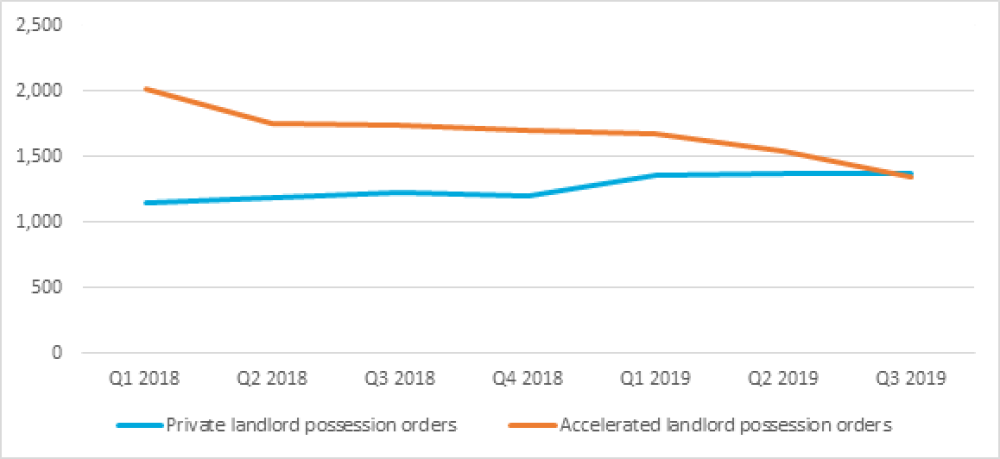

Chart 1 below shows the trends for London in both accelerated possession orders and private landlord possession orders generally.

Chart 1: Number of possession orders granted in London per quarter

Private landlord possession orders are increasing at the same time that accelerated possession orders are decreasing. Unfortunately, accelerated landlord possession order statistics do not differentiate between private and social landlords so it is not possible to identify exactly how much of the decrease comes from the PRS.

However, our previous research found that landlords were significantly more likely to use the accelerated process over the grounds-based possession orders. As such an increase in PRS possession orders should see an increase in accelerated possession orders unless something was forcing private landlords to require court hearings instead.

One potential explanation for this is the judgement in Caridon Property Ltd v Monty Shooltz. This case from early 2018 saw the circuit judge, HHJ Jan Luba QC, rule that failure to provide a gas safety certificate prior to the tenant moving in would prevent landlords from being able to use a section 21 notice, effectively preventing use of the accelerated possession route for the remainder of the tenant’s time in the property.

This would lead to more landlords using the section 8 route which requires a hearing but also requires landlords establish they have a legitimate reason to seek possession against their tenants. As this is more time consuming we would expect to see an increase in the time taken to issue possession orders for private sector landlords overall.

The timing of the biggest drop in accelerated possession orders aligns with this judgement, suggesting that this is the most likely reason for the decline in accelerated orders.

As PRS possession orders increased over this time, it would also suggest that impediments to using accelerated possession do not reduce the number of landlords seeking to repossess properties. It also suggests that landlords have solid reasons for possession as they would have to establish their tenants were at fault before being granted possession under the section 8 regime.

Wait times for possession orders

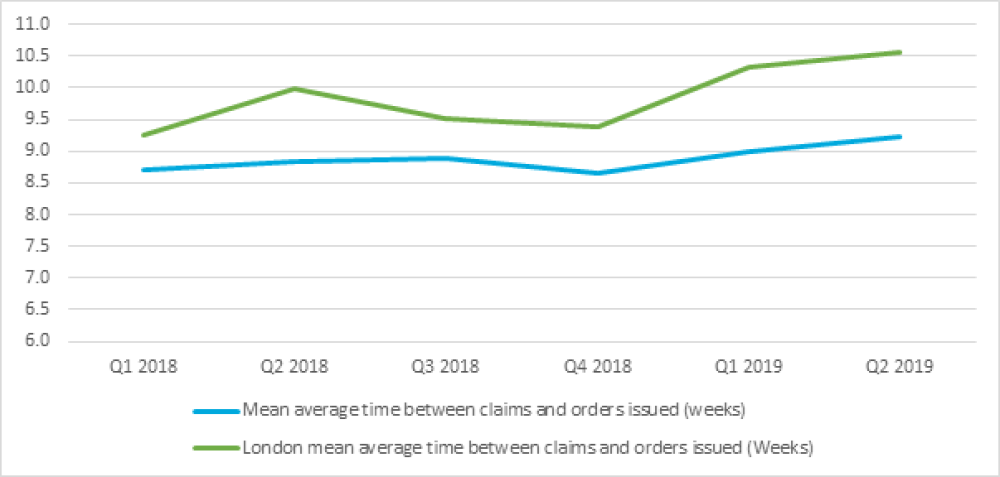

Chart 2 below presents evidence which supports the view that reductions in accelerated possession has no beneficial impact on wait times. In fact the evidence shows the converse is true – the decline in accelerated possession orders has led to an increase in wait times for posession orders:

Chart 2: Comparison of London and national average wait times for the granting of possession orders

As we can see from Chart 2 above, this is the case – the decline in accelerated possession orders has led to an increase in wait times for posession orders. Each quarter in 2019 has seen a significant increase in the wait times for possession orders compared to the same quarter in 2018. Landlords in London must now wait 10.6 weeks for a possession order to be granted.

London landlords also have to wait 15% or 1.4 weeks longer for a possession order than the national average in 2019. This gap also appears to be increasing as London landlords were previously only 7% above the national average at the beginning of 2018.

As a result, landlords in London are waiting more than twice as long as the minimum timeframe for a court hearing and around 2 weeks longer than the maximum expected time.

Wait time for enforcement of a judgement

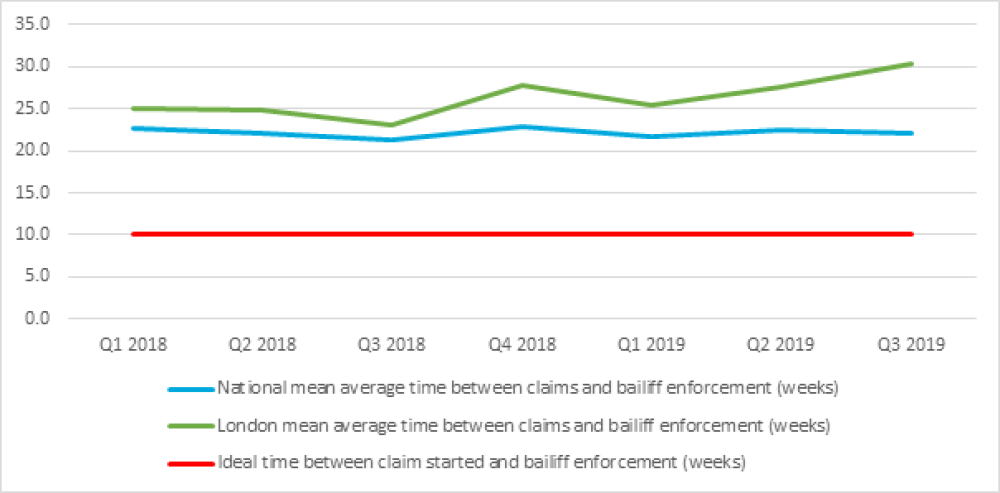

The wait times for possession orders are poor for London and growing worse but this pales in comparison with the issues regarding enforcing judgements in the capital.

Chart 3: Mean average wait times for enforcement of judgements

As Chart 3 above illustrates, London wait times, already higher than average, continued to diverge significantly from the national average in 2019. London landlords now wait on average 30.3 weeks for a bailiff to enforce judgements.

The wait in London is now eight weeks longer than the national average and over three times as long as the benchmark suggested by the CPR. In Quarter 3 2019 alone, London mean waiting times increased by 31% compared to the same quarter in 2018.

Given that most possession orders relate to rent arrears, this is clearly far too long to wait for justice to be enforced. In a situation where the tenant has stopped paying rent, the whole process including service of a section 21 notice would take 39 weeks in total. With median average rents for London at £253 per week this would equate to £9,867 in lost rent over the period where the tenant stopped paying rent entirely. It is little surprise then that London landlords are less confident than any other area of England and Wales.

What are the reasons for these delays?

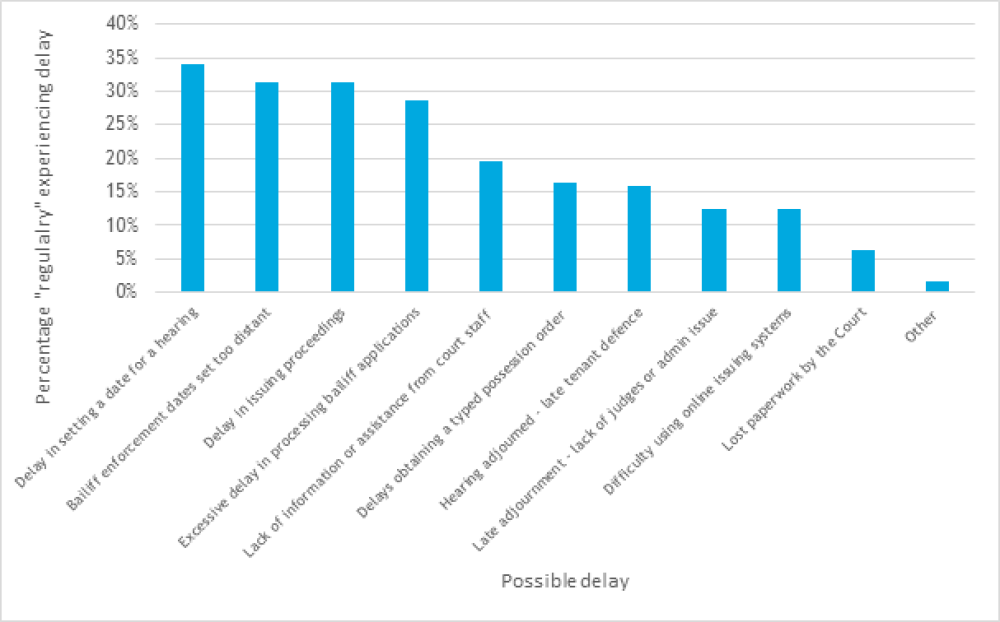

Given the scale of the problem with enforcement in London it is likely that there are a number of factors causing the excessive delays. Previous research by the NRLA asked landlords that had used the courts to identify the reasons behind the delays they had experienced. These answers are reproduced here as they are likely to be indicative of the main causes.

Chart 4: Reasons why landlords had regularly experienced delays with the courts

While a delay in setting a hearing date is the most common reason for a delay, this is to be expected. The majority of possession orders do not lead to enforcement as the tenant moves out. Only 38% of the possession orders granted in London led to applications for warrants in 2019. As such far more landlords will experience delays involving the court than they would the bailiffs.

Nevertheless, it is notable that four of the top six reasons would directly lead to delays in the enforcement of judgements. There were 31% of respondents who cited long waits on bailiffs arriving and 29% experiencing excessive delays in processing bailiff applications. In addition to this, the 17% of respondents who did not receive a possession order in a timely fashion would also struggle to enforce a judgement. Finally, the 20% who struggled with the lack of assistance from the courts would likely also struggle to proceed to enforcement.

The majority of the reasons given by respondents for delay would suggest that the courts do not currently have the resources they need to provide effective enforcement. In particular, given the scale of the delays it is likely that there are insufficient bailiffs in the London area to enforce judgements and more needs to be done to recruit, train and retain bailiffs.

In addition, an unexpected increase in warrant applications cannot explain the rise in wait times for bailiffs. While possession orders have increased over the same period, warrant applications were 16% lower in Quarter 3 2019 than Quarter 3 2018. This suggests there may have been a decrease in the number of bailiffs since 2018.

Are improvements likely?

As the Queen’s Speech has made clear, the Government is intent on removing section 21 notices from the landlord’s toolkit.

Due to the decline in accelerated possession usage over the period covered in this analysis, London is likely to be a useful barometer of how this may impact on the court system in the future. As such, it is likely that if section 21 is removed without a number of complimentary reforms, the delays to seeking possession will increase, not reduce.

A particular area of concern is around anti-social behaviour. Our research found that over half of landlords who had used section 21 did so at least in part because of anti-social behaviour. When section 21 is removed these cases will need to be dealt with via court hearings. Using section 8 for anti-social behaviour is a risk. Cases often fail due to the high evidence requirements and its status as a discretionary ground. These cases also require substantial time for hearings placing a greater strain on the court’s resources. Inevitably this is going to increase the time taken to deal with possession claims.

Unfortunately, this is likely to cause distinct difficulties in London. With the city housing 40% of all HMOs if anti-social tenants cannot be removed relatively quickly then the victims will be forced to live in the same home with them for longer. The Victims Commissioners Final Report has identified that the slow pace of addressing anti-social behaviour is failing the victims at present. Rather than fixing this issue, this is likely to become worse.

Similarly, the best way of ensuring the courts can maintain their current timeframes is to ensure accelerated possession is available where appropriate. Common grounds like rent arrears could be transitioned to the accelerated route to help reduce wait times.

Conclusions

From February 2018, successful possession order applications increased in the London area, while accelerated possession orders fell over the same time. This has gone hand in hand with delays in processing these applications and enforcing the judgements.

Landlords are still successfully gaining possession even after these delays so it is likely that section 21 is masking poor tenant behaviour as they are still proving they have a legitimate reason to gain possession.

This suggests that prior to implementing the section 21 change, the Government needs to take action on a number of fronts to ensure the smooth running of the court system:

- They must sufficiently resource and staff the courts to cope with the increase in the complexity and volume of section 8 hearings.

- It is imperative that a number of section 8 grounds are moved to the accelerated route to free up available court time for the influx of anti-social behaviour and damage related possession claims. The NRLA’s previous research found over half of section 21 cases involved at least some element of damage to the property or anti-social behaviour. As these cases generally require substantially more time for hearing in court this will inevitably negatively impact on the efficiency of the courts.

- The courts need to make more effective use of their powers to shorten the timeframe for holding hearings, especially in cases where anti-social behaviour in HMOs is occurring. In particular, where anti-social behaviour occurs in a HMO, the case needs to be fast tracked. To protect the victims where anti-social behaviour is identified, possession should be mandatory.

- If this is not possible then consideration should be given to allowing HMO properties to continue on with the assured shorthold tenancy regime so that tenants suffering from anti-social behaviour do not have to provide evidence against the tenant they live with.

- Action needs to be taken immediately to improve wait times for bailiffs. The NRLA recommends either privatising the bailiff system to open it up to additional suppliers or allowing landlords in London to automatically transfer enforcement up to the High Court so they can use the far more efficient High Court Enforcement Officers.

- To ensure that the increase in complexity in possession cases does not lead to excessive delays or costs to landlords or tenants, further attention should be paid to implementing a housing court so that cases can be dealt with expeditiously and fairly in front of a judge who is specialist in housing law.

This blog post has been written by James Wood. James works for the NRLA but the views expressed here are his own and not necessarily those of the RLA.

This post benefitted from comments given by various members of the NRLA including Aidan Crehan, John Stewart and Nick Clay.

Note the data presented here has been collected from Freedom of Information requests. It is impossible for the NRLA to verify the accuracy or otherwise of the data.